Piccolo profilo biografico di un grande della Scienza

25 novembre 2013

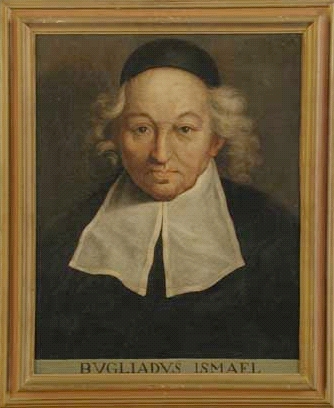

Ismaël Bullialdus nacque a Loudun, in Francia, il 28 settembre 1605. Era figlio di genitori di fede calvinista e suo padre, di professione notaio, era un astronomo dilettante che gli trasmise la medesima passione per il cielo stellato.

All’età di 21 anni si convertí alla fede cattolica e all’età di 26 anni, completati gli studi filosofico-teologici venne ordinato sacerdote. Un anno dopo, nel 1632, si trasferí a Parigi dove, grazie alla famiglia de Thou, egli lavorò per 30 anni, insieme ai fratelli Pierre e Jacques Dupuy, nella Bibliothèque du Roi, la prima biblioteca di Francia. In tale posizione ebbe anche l’occasione di accompagnarli nei loro frequenti viaggi in Italia, in Olanda e in Germania alla ricerca di nuovi libri. Dopo la morte dei fratelli Dupuy, Bullialdus divenne segretario dell’ambasciatore francese in Olanda. In qualità di scienziato Bullialdus fu a stretto contatto con le piú grandi autorità scientifiche dell’epoca, con le quali strinse spesso anche solide amicizie, fra questi sono da annoverare Pierre Gassendi, Christiaan Huygens, Marin Mersenne, e Blaise Pascal. Fu anche un acceso sostenitore delle cause di Galileo Galilei e di Niccolò Copernico.

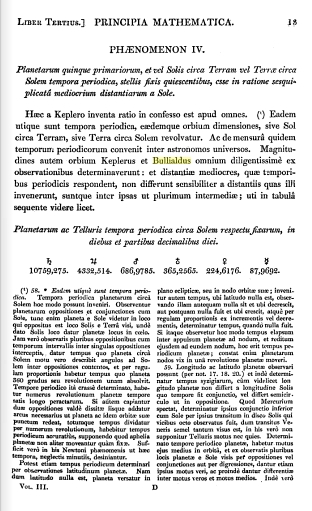

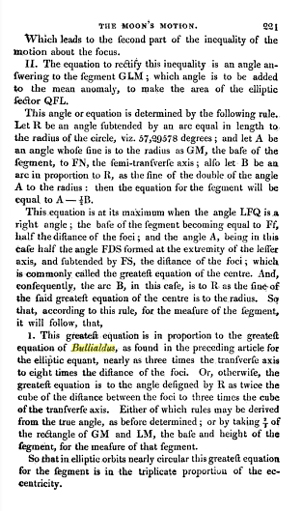

Nel 1645 Bullialdus pubblicò l’opera Astronomia philolaica, nella quale propose che la forza di gravità seguisse la legge del quadrato inverso. Isaac Newton constatò che questa ipotesi era giusta e nella sua celebre opera Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica riconobbe l’opera di Bullialdus, del quale citò la teoria, facendo uso delle sue accurate tabelle di osservazione: «And as to the measures of the periodic times, all astronomers are agreed about them. But for the dimensions of the orbits, Kepler and Bullialdus, above all others, have determined them from observations with the greatest accuracy; and the mean distances corresponding to the periodic times differ but insensibly from those they have assigned, and for the most part fall in between them; as may be seen in the following table» (cfr. NEWTON, Phenomenon IV, III, 1846, 388)).

Alcune pagine dell'opera di Isaac Newton, Philosofiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, III, 18.221 dove

lo scienziato inglese cita l'opera di

Ismaël Bullialdus

Nel 1667 Bullialdus pubblicò l’opera Ad astronomos monita, nella quale tra l’altro annunciò la scoperta che le variazioni di luminosità della stella Mira Ceti erano, oltre che regolari come già precedentemente noto, anche irregolari, scoperta fatta alcuni anni prima da Johannes Hevelius. Fece egli stesso una serie di osservazioni di tale stella, giungendo alla conclusione che, analogamente al Sole, la stella doveva avere delle macchie, e che le variazioni regolari erano dovute alla rotazione sul suo asse, mentre quelle irregolari erano dovute ad alterazioni delle sue regioni oscure. Tale ipotesi sulle stelle variabili era - come oggi sappiamo - errata, ma all’epoca fu accettata come valida e tale rimase fino all’Ottocento inoltrato (cfr. HOSKIN M., Storia dell’Astronomia di Cambridge, ed. Rizzoli BUR, Milano 2001, 159).

Dopo una disputa con l’ambasciatore francese d’Olanda, nel 1666, venne destinato al Collège de Laon, dove si occupò della biblioteca. Bullialdus pubblicò la sua prima opera De Natura Lucis nel 1638, cui seguirono altre opere. Fra di esse figura anche la sua corrispondenza relativa al periodo in cui fu coinvolto nella “Republic of Letters”.

La “Republic of Letters” era un’iniziativa volta a favorire la corrispondenza fra gli intellettuali o i “philosophes” come venivano chiamati in Francia, nel corso dei secoli XVII e XVIII. La “Repubblica” divenne cosí una sorta di comunità internazionale virtuale di studiosi e letterati che si scambiavano lettere, articoli pubblicati e opuscoli, cercando di estendere sempre piú la loro rete di scambi.

La corrispondenza di Bullialdus venne man mano raccolta e costituí cosí quello che sarebbe stato l’Archivio Boulliau. L’archivio purtroppo subí nel corso del tempo vari danni. Poco dopo la sua morte o, come alcune ricerche hanno dimostrato, forse anche poco prima, l’intera sua biblioteca, i libri, i manoscritti e la corrispondenza, furono dispersi. L’intero archivio Boulliau venne venduto e per un secolo venne via via disperso, anche a causa di furti e incidenti, per tacere dei falsi che apparvero sul mercato.

Fortunatamente la Bibliothèque du Roi, prima del 1782, acquisí una gran parte delle carte. La Collezione Boulliau contiene attualmente 41 volumi e oltre 23.000 pagine. I documenti sfuggiti a tale archivio comprendono circa 7.000 pagine di manoscritti oggi dispersi in circa 45 diversi archivi e in una dozzina di paesi circa.

Boulliau Ismaël - XVIII sec. - Olio su tela, Università di Bologna

Numerose ricerche hanno reso possibile un inventario completo della collezione Boulliau e un calendario cronologico della sua corrispondenza. Molto materiale purtroppo è andato definitivamente perduto. L’ultimo testamento di Bullialdus, datato 20 agosto 1691, non fa alcuna menzione dei suoi manoscritti.

Una parte ingente del lavoro archivistico volto a ricostruire la documentazione storica è stato portato avanti da Robert A. Hatch che ha pubblicato un’opera intitolata: Archives of the Scientific Revolution. The Formation and Exchange of Ideas in Seventeenth-century Europe, edited by Michael Hunter, The Boydell Press, Woodbridge 1998.

Le lettere piú famose incluse nell’Archive Boulliau includono corrispondenza con nomi di rilievo come Galileo, Mersenne, Oldenberg e Huygens. Le lettere meno note riguardano Pierre Desnoyers, Fermat, Gassendi, Nicolaas Heinsius e il Principe Leopoldo. La maggior parte della corrispondenza e dei manoscritti di Bullialdus rimangono tuttavia inediti.

Bullialdus fu uno dei primi membri di lingua straniera scelti a far parte della Royal Society di Londra. Ciò avvenne il 4 aprile 1667, solo sette anni dopo la fondazione della società.

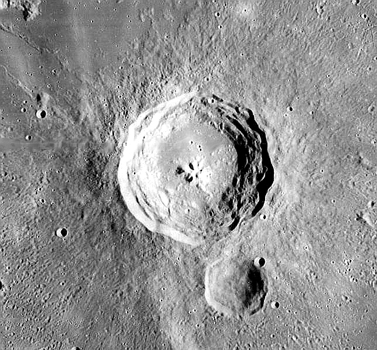

Gli ultimi cinque anni della sua vita Bullialdus li trascorse svolgendo il suo ministero sacerdotale nell’Abbazia di San Vittore a Parigi. Ivi morí all’età di 89 anni, il 25 novembre 1694. In suo onore gli venne dedicato un cratere lunare.

Elenco delle opere principali:

De natura lucis (1638).

Philolaus (1639).

Expositio rerum mathematicarum ad legendum Platonem utilium, translation of Theon of Smyrna (1644).

Astronomia philolaica (1645).

De lineis spiralibus (1657).

Opus novum ad arithmeticam infinitorum (1682).

Ad astronomos monita duo (1667).

**

Il cratere meteoritico lunare Bullialdus localizzato nella parte occidentale del Mare Nubium

Ismaël Bullialdus Biography

Article by J. J. O’Connor and E. F. Robertson

From The MacTutor History of Mathematics archive

[http://www-gap.dcs.st-and.ac.uk]

Ismaël Boulliau’s mother was Susanna Motet and his father was Ismaël Boulliau; both were Calvinists. Ismaël Boulliau, the father, was a notary by profession but was an amateur astronomer who made observations in Loudun. His son, the subject of this biography, described him as having:

«...a very clever mind and a character suited both to seriousness and pleasantness».

Susanna and Ismaël Senior had their first son on 3 August 1604. He was called Ismaël after his father but he did not live. They then called their second child, who was born in the following year, Ismaël. He did survive and become a famous astronomer and mathematician. He is the Ismaël Boulliau of this biography.

Let us note that there was in Loudun an important circle of intellectuals of which Ismaël Boulliau Senior was part. They met in a local hotel and provided a focus for other visiting scholars. It was important for the young Ismaël who attended these meetings and became acquainted with many leading men of the day. Certainly as the young boy grew up he was taught about astronomy by his father although he studied law and the humanities rather than science. We know that Boulliau’s father observed the comet of 1607 which would later be called Halley’s comet. He also observed another comet in 1618 when his son was 13 years old. This must have been an exciting event for both father and son, and Boulliau later published details of his father’s observations of these comets in his famous treatise of 1645.

Boulliau was brought up a Calvinist by two Calvinist parents. However when he was 21 years old he became a convert to Roman Catholicism. By the age of 26 he was ordained as a Catholic priest and one year later, in 1632, he went to Paris. There he worked as a librarian associated with the brothers Pierre and Jacques Dupuy who were working on the Bibliothèque du Roi. This library, which dated back to the fourteenth century, was moved to Paris between 1567 and 1593. It had been catalogued in 1622, ten years before Boulliau arrived in Paris, and Pierre and Jacques Dupuy travelled throughout France amassing books and manuscripts for the library. The de Thou family were also heavily involved with the Bibliothèque du Roi, and they provided financial support for Boulliau in his work as a librarian. Boulliau had the right skills for the work he undertook, for he was a broad scholar with a deep interest in history, philosophy and classics, yet equally at home in the scientific circles of Paris where he began to shine building on the firm foundations in astronomy taught by his father.

In his capacity as librarian Boulliau travelled widely in Italy, Holland and Germany buying books. In 1657, after the death of his two employers the brothers Dupuy, he worked as a secretary to the French ambassador to Holland who was a member of the de Thou family. He was to work again as a librarian, this time for the same French ambassador de Thou, but after a dispute with him in 1666 he lived at the Collège de Laon. He spent the last five years of his life in the same occupation in which he started his career, becoming a priest at the Abbey St Victor.

Boulliau was a friend of Pascal, Mersenne and Gassendi and supported Galileo and Copernicus. He published De natura lucis (1638) which was based largely on the discussions he had been having with Gassendi on the nature of light. He certainly did not agree with Gassendi’s atomic theory but took his own three dimensional view of light. His next work Philolaus (1639) had in fact been available in manuscript form for some years before it was published. It supported the world view of Copernicus, and is only remarkable in that it must have been quite difficult for a recent convert to Catholicism to openly support such views. His next work was on mathematics, namely his edition of the arithmetic text Expositio rerum mathematicarum ad legendum Platonem utilium by Theon of Smyrna which was the first printed version of this text. It appeared in 1644 and later in the same year he wrote to Mersenne (who was in Rome) on 16 December:

«I think few people have seen my Theon, as only a few copies were taken to Italy. The Dutch and Polish received several».

In 1645 Boulliau published Astronomia philolaica which accepts elliptical orbits for planets. He wrote in the same letter to Mersenne:

«The Astronomia philolaica is finally complete, but I have a quarrel on my hands, as Jean-Baptiste Morin, the Prince - according to his own views - of the whole of Astronomy, has come across something not to his advantage or liking. The simple suggestion I put to him should make him wiser and more reserved in making injurious statements against someone who has never made such cruel remarks, and who has never offended him».

He claimed that if a planetary moving force existed then it should vary inversely as the square of the distance (Kepler had claimed the first power):

«As for the power by which the Sun seizes or holds the planets, and which, being corporeal, functions in the manner of hands, it is emitted in straight lines throughout the whole extent of the world, and like the species of the Sun, it turns with the body of the Sun; now, seeing that it is corporeal, it becomes weaker and attenuated at a greater distance or interval, and the ratio of its decrease in strength is the same as in the case of light, namely, the duplicate proportion, but inversely, of the distances that is, 1/d2».

However he then argues that the sun does not produce a planetary moving force:

«...I say that the Sun is moved by its own form around its axis, by which form it was ignited and made light, indeed I say that no kind of motion presses upon the remaining planets ... indeed [I say]that the individual planets are driven round by individual forms with which they were provided...».

The Astronomia philolaica represents the most significant treatise between Kepler and Newton and it was praised by Newton in his Principia, particularly for the inverse square hypothesis and its accurate tables. There is one aspect of Boulliau’s philosophy which is well worth commenting on - namely the fact that he believed in simple explanations and moreover he wanted many different observed properties to result from a single cause. He did not achieve his aim, that would be achieved by Newton, but at least he set the scene for such developments. He later published further mathematics texts, but they are not of much significance. De lineis spiralibus (1657) related to work by Archimedes and Pappus. Then in 1682 he published Opus novum ad arithmeticam infinitorum which he claimed clarified the Arithmetica infinitorum of Wallis. The other astronomy text worth mentioning is Ad astronomos monita duo (1667) in which he established for the first time the period of the variable star Mira Ceti, a long-period variable. He gave 333 days which is a good estimate and only about one day too long.

Boulliau was a close associate of Huygens who turned to him first with his discovery of the rings of Saturn and sent him pendulum clocks. One of the most interesting aspects for modern research into Boulliau, however, is that he was a prolific correspondent. This correspondence covers about sixty years, between shortly after his arrival in Paris in 1632 and the year before his death. It is also interesting that this correspondence covers 45 years after Mersenne’s death, so we can think of him as filling his role. How many letters are we talking about here? It is amazing to realise that historians have over 5,000 letters and so their assessment is still an ongoing task. They are full of news, much of it trivial in nature, about science and politics.

Although he moved in the circles associated with Mersenne which later became the Academy of Sciences, he was never elected to that body. However, he was elected a foreign associate of the Royal Society in 1667.